- Home

- Colin McEnroe

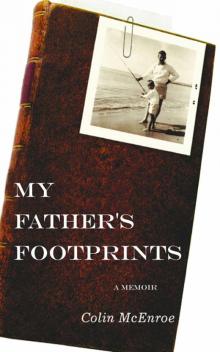

My Father's Footprints Page 5

My Father's Footprints Read online

Page 5

You can’t believe the little bastards.

Fairies are capricious and flighty. In the middle part of his life, they walked out and left him with nothing, no enchanted sword, no book of spells, nothing but the dull ether of the bottle. And in 1970, fairyless and despairing, he played a very dangerous game and almost took the bunch of us down with him. In 1970, he died in a much more serious and frightening manner than this little brush with the heat of July 1976.

But that is a story for later. Or sooner. We’ll come to it eventually, as we work backward through time.

In 1976, Bob McEnroe has played his desperate game. We see him returned from Hades and scorched by a refining fire. His hair, prematurely gray since his thirties, is now white as duck down. On his face, more often than not, is a mysterious half-smile, and it takes the ferocity out of those hazel eyes and that raptor’s beak of a nose.

One day, with very little fanfare, he puts down his three-pack-a-day unfiltered Fatima and Pall Mall habit and picks up a pipe. After a day or two of finding out he cannot smoke a pipe without inhaling, he puts that down, too. And forty years of constant smoking—an addiction so severe he cannot sit through a movie—end with scarcely a remark from him. When I was in the sixth grade, he tried to help me improve my athletic performance by running with me around the school ballfields at night, after homework was done. He ran with a lit cigarette in his hand. I would look out in the darkness and see its tiny orange light sailing and bobbing eerily through the ink. The fairies watched from the bushes.

Tobacco has no power over him now because almost nothing does.

The old stories are full of men who return, much changed, from a trip to the underworld. And it would probably be more erudite to mention Aeneas or Orpheus, but my father reminds me most of Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings, who falls through fire and water to the “uttermost foundations of stone” while battling a terrible monster. When he returns from death, he is different.

His hair is “white as snow in the sunshine,” and his eyes are bright and piercing. And Gandalf tells his friends that, indeed, “none of you has any weapon that could harm me now.”

Robert E. McEnroe battles his dark, fiery beast in 1970 and comes back now in the thrall of a gentler magic. Few weapons can harm him, including death.

He drafts his living will. I reproduce it here.

To my wife, son, doctor, and any relevant wardens, keepers, or turnkeys:

Death must come to all and mine to me. I do not fear death, but dread the thought of living the seventh age of man as a glob of protoplasm connected to tubes which are tied to machines, valves, regulators, blinking lights, and shrill whistles, and where all prognoses are completely negative.

I do not ask those in charge of me to break any laws of God or man, but, if it is possible, I pray that you will pull the plug, throw the circuit breaker, blow the fuse, or pull the main switch. God bless he/she who disconnects the life support. I cannot offer him/her a place in heaven, but I’ll fix up something comfortable in hell.

“Do you seriously expect me to go into court with that?” I ask him.

He shrugs. “Put it under your rubber plant,” he suggests.

This is one of his favorite images. He genially accuses agents and editors of having placed his scripts under their rubber plants. And he hands me various odd and disturbing things to put under mine, not that I have one.

One day—this is before the living will—he approaches me with a folded piece of lined yellow paper.

“You mustn’t show this to anyone,” he says.

“Okay,” I agree.

“This represents my refutation of Gödel’s ‘incompleteness theorem.’”

“Okay.”

“I want you to put this under your rubber plant, in case I get hit by a bus someday.”

“Okay.”

“Gödel’s ‘incompleteness theorem’ is probably the most important idea in all of modern higher math, but I think he’s wrong. I’m pretty sure I’ve got it right.”

The hubris in this statement is almost incalculable. Gödel’s “incompleteness” is, one could argue, almost as important as Einstein’s “relativity” or Heisenberg’s “uncertainty.” (And they’re all cousins at the twentieth-century family picnic of throwing up one’s hands over the whole question of precise knowledge.) The only difference is that fewer people have heard of Gödel because nobody really cares whether higher math works or not.

Saying you can disprove Gödel is like saying you can prove ice is really air or that outer space is really black velvet draped over an aluminum frame or that Ulysses is really the Dublin phone book.

My father is a polymath, a voracious reader, and a grandiose dabbler with crackpot tendencies. He has been reading extensively about higher math and is just the type to conclude that he has imploded one of the pillars of the field. Now he stands before me in his wool dress slacks and the rumpled white dress shirt he wore showing houses the day before and asks me to join him in this delusion.

“That’s… great,” I tell him.

“You can’t show it to your friends.”

“I’m not sure I’d want to.”

He leaves, and I sit there for a while trying to picture myself spilling the beans to my friends: “Hey, Stinky, my dad has cracked Gödel’s theorem. What’s your dad up to?” Nyah, nyah, nyah.

There is a rule of thumb in the newspaper business. One of my editors used to call it the “Three-Minute Mile Principle.” It’s almost as important as Gödel’s “incompleteness.” People show up in newsrooms claiming to have done all kinds of breathtakingly improbable things. Assassinated the premier of Hungary using oven cleaner and margarine. Held prisoner by talking leopards. Spotted Barry Goldwater spreading banana peels on the Chappaquiddick bridge. And if they’re telling the truth, you’ve got a great story. The problem is, they’re usually not, and quite often they themselves don’t know that they’re not. The Three-Minute Mile Principle is a kind of information triage. It says that you can’t spend too much of your life checking out all kinds of nutball contentions. If somebody shows up claiming to have run a mile in three minutes, he probably hasn’t.

Should there be a corollary that says, “On the other hand, if you don’t check out the wildest assertions, you’ll miss Watergate; you’ll spend your career confirming and reconfirming the dull normal”?

No. We don’t need that rule. You go into the newspaper business because you believe or at least hope that the fabulous is sometimes true, that giants do walk the earth, and that the tip about machine-gun-wielding teenaged dropouts forming a secret commune at an abandoned marina on the river is real. You tell your editor you’re going to drive down there and check it out, and she says, “Good,” because she’s the same way. We don’t need any reminder to keep a certain dreamy romanticism alive in our work. We had fathers who talked to fairies and who claimed to be secret math geniuses, fathers who took their pre-Christmas paychecks to the racetrack and hoped the kids would remember the year they came back with the best toys ever.

So when it comes to Bob McEnroe vs. Gödel, screw the Three-Minute Mile Principle. Sitting there with that paper in my hand, I really believe he’s done it. What choice do I have? One-third of my identity, roughly, is bound up in the belief that this man with the unruly hair and the permanently distracted look, with his head bowed and his eyes sliding over into an unseeable crack in the universe, this man is an overlooked genius.

Without having to be told, I know that he is worried about piracy. What if someone, somehow, got hold of his proof (or disproof) and claimed it as his or her own? His only hope is to publish it under his own name, but what journal of mathematics is going to listen to a real estate agent and former Broadway playwright with no formal education in higher math (his recent incarceration in a psychiatric facility being very much the cherry on the Crackpot Parfait)? I know also that, in my dad’s mind, this mathematical insight is some kind of souvenir from his supernatural travels, a pale flower plucked from

a path in the underworld or an elf-cake baked by the little people.

The little people. He stays up late, communing with them and (more than I know) tippling. They’re the ones who have him thinking he’s a math genius.

He needs to get it set in type, published, so that he can prove he was the first to refute Gödel. But if he approaches anyone with this idea, he’ll be dismissed, he knows, as a crank.

“I have a fiendish plan,” he tells me one night.

“Oh?”

So what’s your father up to?

“The bottom rung on most ladders is a cell, a place to lock away those who might do harm if left free to roam. There are different kinds of cells and they make up a ladder of their own. At the top is the luxury cell, which is set aside for dictators, kings, and presidents. This story is concerned with a cell at the very bottom. It holds a naked mental patient. His mind has been in a fugue state for five years. He is incontinent. He is washed by a hose. His food is prepared in chunks like dog food. He cannot be trusted with a knife or fork.”

These are some notes by my father for his novel The Nemo Paradox.

My father has never been inclined to do harm, but he knows what it is like to wake up from a coma and find his hands and feet tied to the frame of a hospital bed, to have only the dimmest sense of how he arrived there, to have the daunting and exhilarating task of rebuilding his life from a point of implosion.

From this starting point he constructs a novel. He has never written one before, and I’m not even sure he likes them that much. He plunks himself down at the dining table and writes. Late at night, when my mother and I have given up, gone to bed, he’s still writing and—I now see—probably drinking.

The plot concerns a man named Henry Nemo, accused of terrible crimes and treated, because of his thundering rages, to a lobotomy. Nemo wakes from surgery with no knowledge of his identity or past. He reconstructs the world ab ovum and when he learns of the accusations, he escapes from a state mental hospital with the intention of finding himself either innocent or guilty.

Henry Nemo is huge and hairy and dirty and horny.

We have temporarily abandoned fairies and taken up, instead, with a giant.

The Nemo Paradox is its own kind of paradox. It is, in places, poetic, charming, funny, cosmic. “God made the universe—a trillion trillion spinning balls of fire. What did he want a universe for?”

It is, in other respects, crude, hostile, and simplistic. It seems unnaturally concerned with sustained erections and sexual prowess. Most of its women characters exhibit odd and disturbing sexual appetites. If your father had written it, it would give you the creeps. You would start to wonder what was running through his mind when he took you to the zoo or played whiffle ball with you. Here is an example of what I mean and—trust me—I’ve made a point of staying away from the truly vivid, visceral, and viscous.

“She put her feet on the coffee table so that her thigh pressed against me. I did what anybody else would have done and kept right on doing it until she went from 98.6°F to 102°F. At 102°F her pulse was at 180 and her sweater and slacks were in a pile on the floor. Her central nervous system rang her engine room for steam and got it. She started to writhe like a snake on a hot bed of coals. She moaned, trembled, clawed, bit, whispered obscenities in eight languages. Her hips rotated on a vertical axis, while her pelvis boxed the compass. The effect was gyroscopic and tremendously alive.”

Yeesh.

His career as a successful Broadway playwright lies fifteen years in the past, but he finds a William Morris agent named Ramona Fallows and courts her.

“Dear Ms. Fallows,” he writes, when she has been too long in responding to his second manuscript submission, “I have been trying to think of ways to get The Nemo Paradox out from under the rubber plant.

“The proposal I have strikes me as being dubiously arithmetical, but it’s all I have.

“I suggest you read the last forty-nine pages, starting at page 181. If you like this material it will mean that, by adding the material you like in the first version to the forty-nine pages, you approve of 77 percent of the novel. (177/230)

“Of course, there are people who are immune to the charms of arithmetic, and lots of people don’t go near rubber plants for months.”

Three months pass, and he writes her again.

“Dear Ms. Fallows, I dreamed about The Nemo Paradox. In my dream the script was under a seven foot rubber plant in the corner of a large waiting room. The script was squashed down by the weight of the tree. Bits of rubber leaf and rubber-tree spores circled the tree with elastic detritus. As I watched, a small boy used the planter as a urinal. I had the feeling that the script had been forgotten—that whoever had put the script under the tree had left the publishing business and gone into real estate.

“There is no particular reason why you should interest yourself in my dreams. It’s just that I haven’t got anybody else to tell them to.”

I am an adolescent when this is written. If you think he doesn’t intend for me to see myself in the small boy pissing on his manuscript, if you think he doesn’t intend for me (and the rest of the universe) to sigh at the notion of his having no one to tell his dreams to, if you think he does not intend for me to find this letter someday—well, you should know that he makes three or four copies of it and sprinkles them through his files.

He does more rewrites and contacts her again.

“The book is finished,” he writes to Ramona. “It contains:

2 murders

143 grammatical errors

6 acts of intercourse

847 misspellings

1 lesbian relationship

1,131 corrections made with Liquid Paper

6 B & Es

1 unlikely love story.”

I am tempted to say that a second unlikely love story ensues—that of Ramona Fallows’s affection for my father’s ugly-duckling book. It is nearly impossible to like, but she embraces it anyway.

Alas, no one else does, although virtually everyone else agrees the ingredients for a very good novel seem to be moiling around in the book’s innards.

“He writes with real humor and sensitivity—rarities both,” says one editor in a lengthy letter to Ramona Fallows about why, ultimately, he is not taking the book. There are a lot of these letters, longer and more ambivalent than most rejection notes. Reading them now, I feel a sense of helplessness on my father’s behalf, coupled with a slight unease, as if something in these letters might be contagious, as if something might travel from him to me and push my writing one or two degrees south of saleable.

The letters themselves are so full of little apologies and half-compliments and flashes of enthusiasm that they make a kind of blizzard before my father’s eyes, obscuring from him the inevitable truth. Nobody is going to buy this book because nobody likes it. I mean “like” the way you like a dog or your best friend Fred, not the way you like Mozart or Heaven Can Wait. There’s something a little snarly and uncongenial about this novel.

“If only I’d liked this a little better, all of the above, it seems to me it could be cured by rewriting and editing,” writes an editor at Random House. “But unfortunately, I simply don’t like it well enough to want to undertake the job…”

What is not in any of the letters to or from anybody, what is not confessed to Ramona Fallows, what is not detected by any of the dozen or so editors to read the book is this:

Henry Nemo, our family giant, is afflicted by visions and dreams. Like my father, who can’t stop thinking in numbers whether he is writing sex scenes or courting Ramona’s approval with unwieldy fractions, Henry has integers flying through his head. Odd progressions pop into his mind, shards of memory from his obliterated life. Taken together, these fragments constitute something my father is desperate to preserve between two covers, with a copyright date and a Library of Congress number.

Once The Nemo Paradox is published, you see, he plans to inform the world that these fragments, these prio

ns of cognition sloshing around in Nemo’s mind, constitute his refutation of Gödel’s “incompleteness.”

One day at a small family gathering, my father, in a tone of resigned good cheer, tells my future wife, “I have made every mistake that a man can possibly make.”

Every family nurses, as part of its oral history, the plot twist of the missed opportunity, the fortune squandered, the unseized chance that would have led to wealth. Everybody has a grandfather who turned down the offer to be fifty-fifty partners with Henry Ford, or who drank and pissed away an enormous sum, picking up checks for ne’er-do-well friends, or who sold land for a pittance, only to see it become part of the Atlantic City board-walk.

This is the Universal Fiasco, the Edenic fall of every clan. The only families exempted, I suppose, are Rockefellers and Gateses and Buffets, people who cannot plausibly claim to have let prosperity slip away. What do they do for rue? I suppose it sprouts up in other forms.

In my family, the sense of The Fall is more finely grained, worked into every observation like neat’s-foot oil into a baseball mitt. We are more fallen than not fallen. Everything has gone wrong, except on those rare, treasured occasions when things have gone right.

My grandfather makes and loses a million dollars in the 1920s. In the fall of 1947, my father does the unthinkable. As an unknown playwright living in a Hartford, Connecticut, boarding house, he sells two different scripts to two different Broadway producers on the same day. The New York papers can’t come up with anything to compare it to. My father becomes the hottest new playwright in New York, and then, after 1948, gets exactly one more play produced in the last fifty years of his life.

He does not stop writing plays, mind you. The scripts are heaped up around me now like the skeletons of the conquered. They’re sealed up in polythene envelopes and stacked next to the unpublished novels. All of them are invisibly roped together by a winding skein of bad decisions—writing projects refused and calls unreturned. A stint in Hollywood from which he fled, like Lot from Sodom. Errors unrelated to writing. He shrewdly buys a lot on what becomes the most desirable road in desirable Farmington, Connecticut, and later sells it for exactly what he paid.

My Father's Footprints

My Father's Footprints