- Home

- Colin McEnroe

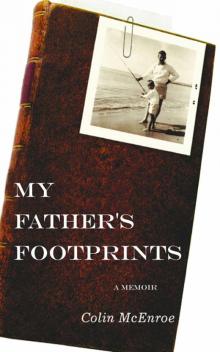

My Father's Footprints

My Father's Footprints Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2003 by Colin McEnroe

All rights reserved.

“Telemachus’ Detachment from Meadowlands by Louise Glück. Copyright © 1996 by Louise Glück. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

Material from “Faerieland” by Colin McEnroe in Northeast Magazine, June 21, 1992. Copyright The Hartford Courant. Reprinted with permission.

“Let’s Wait” by Pablo Neruda, copyright 1992. Reprinted by permission of Grove Atlantic.

“I Wouldn’t Bet One Penny,” published by Warner Chappell, copyright 1961 by Johnny Burke; copyright renewed 1989 by Mary Kramer, Rory Burke, Timolin Burke Goldfarb, and Reagan Drew. Reprinted by permission.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: December 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56637-7

Acknowledgments

My friend, colleague, and in-law Steve Metcalf used to play the organ in a gospel church, and when it came time for members to stand and give personal testimony, a certain woman would rise and mention—among the many blessings afforded her by heaven—“My friends all know me.”

The meaning of this is obscure and, in another way, obvious. It’s sort of the ultimate acknowledgment. If my friends all know me, what else do I need to say?

(My secret fear is that I will acknowledge people who were barely aware of this project and whose absentminded “hmmmph”s and “mmmmmmm”s I over-embraced as encouragement. And now they see their names here and think: I was one of his pillars? He must be desperate.)

This project took shape mainly with the help of my old colleagues at the Hartford Courant, led by Kyrie O’Connor and Lary Bloom, and with the support of Men’s Health magazine, where Peter Moore and his crew took a chance on an essay that became chapter one of this book. The Books for a Better Life people honored that essay and drew the attention of Warner Books. Many thanks to the endlessly patient Karen Melnyk and her successor, Katharine Rapkin.

Esther Newberg is my agent. So watch out.

I thank also my colleagues at WTIC for putting up with my absences and states of distraction. I had friends who helped in ways immeasurable and measurable. These include Peter and Sally Shapiro, Bill Curry, Denise Merrill, Jessie Stratton, Frank Rich, and Bill Heald. Susan Campbell did not hit me (even) once during the writing of this book.

Epic gratitude to Luanne Rice, all-knowing, all-seeing, all-giving, and Anne Batterson, who rescued me and my book from all kinds of mistakes.

Thanks to the good people of Mountnugent, especially those mentioned in chapter five, and to Susan McKeown, for the inspiring music of “Lowlands.”

Some of the names in this book were changed, but I’m not saying which ones.

Thanks to all of you who believed in my father’s work, during his life and afterward. Thanks to all the family members who supported me, especially my wife, Thona, and son, Joey. For rights to use Joey’s image in “My Father’s Footprints—The Video Game,” you need to negotiate directly with his people.

And thanks most of all to my mother, who could have vetoed the whole idea and didn’t.

Contents

Copyright

Acknowledgments

Preface

1. Seal Barks and Whale Songs

2. Why Nobody Understands Turbulence

3. Bliss

4. MOST HaPPy FIMLY

5. Straight Outta Roscommon or Why History Can Be So Hortful

6. In Which the Court Adjourns

Epilogue

When I was a child looking

at my parents’ lives, you know

what I thought? I thought

heartbreaking. Now I think

heartbreaking, but also

insane. Also

very funny.

“TELEMACHUS’ DETACHMENT”

BY LOUISE GLÜCK

Preface

On the most beautiful evening of the spring of 2002, we ride our bikes, Joey and I, and somehow wind up at the grave.

Joey is twelve now, four years older, very different, and yet exactly the same as the boy you will meet in this book. Embedded in the earth is a small granite slab into which his grandfather’s name has been cut. He doesn’t like to see me step onto it.

“Don’t stand on it!”

“Why not? Bob’s not here. He’s not underneath this stone.”

Joey climbs up on a reddish-brown boulder next to the grave. My mother and I picked the site partly because of the boulder.

“Where is he?”

“Maybe in the air around us.”

In the pine trees behind the boulder, someone has hung chimes, and they ding softly in the breeze.

“Is that it? Is he in the air around us? Or is it: When you die, you die?” Joey demands.

“Some people think that.”

“Is that what you think?”

“I think it’s possible that we become something greater.”

“What does that mean?”

“Well,” I fumble, “when we’re in these bodies… we suffer from sorrow, need, guilt, hunger, pain, fear…”

“Dad, that’s your life,” he interrupts, and I laugh. He laughs, too.

“What I was going to say,” I resume at last, “is that maybe when we die, we become something more pure and more joined-together with everything else. Maybe we move beyond those limitations of sorrow and pain.”

“Maybe we’re born into another body,” Joey says. “Maybe it’s like one of my video games. You have to get to Level Ten before you get out.”

We fall silent, and only the chimes speak.

“This is movie-like, with the ringing,” he says at last. He gestures in a way that takes in the whole scene and, I think, the conversation. “It’s like a movie.”

I look at him, and love, dark and fiery, rips through me. He has thickened with preadolescent chunkiness. Wriggling into his Latino identity, he has been hanging with the Puerto Rican kids at school, cribbing their fashions. He wears chains and robin’s egg–blue Carolina football shirts and bulky dark denim shorts that droop to the knee. He is a long way from the little boy who darted like a beach bird across the early days of this story. I will love him with every drop of my lifeblood no matter who he is.

We get our bikes and ride home swiftly. I want to write it all down before it changes in my head. And I do, scribbling it verbatim onto a series of five Post-Its, the first pieces of paper I find.

But first there’s the bike ride out of the cemetery with the sun low in the west, like a hole in the sky-side, letting the gold stream in, across the trees, heavy with spring flowers, across the stern white slabs of the dead.

Emerson said heaven walks among us, so maybe my father is here, gleaming in all that slanting golden afternoon light.

One

Seal Barks and Whale Songs

Sarah Whitman Hooker Pies recommended with this chapter

Mother Teresa’s Mouse Pie for religious cats, bats, and owls

Westinghouse Six-Stroke Air Pie with jelly beans and old subway tokens

The Green Bastard

The last time my father died was in 1998. It differed from his other deaths in that, this time, we buried him. The McEnroes were, until recently, the sort of Irish-American family that favored florid Irish wakes. I remember my parents returning from one of the last good ones, around 1970. They were pretty well lit, and my mother explained that one of the McEnroes, a man in the liquor business as it happened, parked a station wagon loaded with potables in the funeral home parking lot. The mourners would filter out there,

have a nip, and return to the parlor, their enthusiasm for the wake and their nostalgia for the dead vastly refreshed.

Their bodies heavy with weeping and their minds sodden with drink, they eventually managed to lock the keys inside the station wagon. Very quickly, it came to pass that getting the station wagon unlocked was the thing of paramount importance, so that virtually everyone who had been inside the funeral home was now out in the parking lot giving advice and jiggling coat hangers. The poor corpse was left alone with one or two sniffling women.

My father was faintly amused, but it was, he said, a puny affair compared to the wakes of distant summers.

“Then,” he said, “the women would keen, making such an awful high-pitched racket you thought you were going to lose your mind. And when the men were drunk enough, they’d haul the body out of the casket and prop it up in a chair, put a drink in one hand and a cigarette in the other.”

He paused and smiled, letting his hazel eyes wander up in the air to where the memories floated like dust motes.

“The whole idea,” he said, a little dreamily, “was to make sure the son of a bitch was really dead.”

The last time my father died, the son of a bitch really was.

It starts in 1996.

I’m with my father, on a spring afternoon in West Hartford, Connecticut, where we all live, watching my son, who has just learned to ride his bike.

Where we live, the forested reservoir lands are also parks. Paved roads, dedicated to hikers, joggers, and bikers, curl and course through the gorgeous woods.

I see Joey launching himself onto those roads, sailing away in looping arcs, out to where my father cannot follow.

Joey is adopted. He is Mexican, and his skin is the beautiful color of coffee ice cream. In the summer, it deepens into a coppery chocolate. His eyes are wide and brown and startling.

My father’s hair is white as summer clouds, and his skin is ruddy from rosacea and Irishness. His body is thickset. In appearance, he has been compared, variously, to Chet Huntley and Spencer Tracy, although neither was ever as handsome, or as fey, as my father in his prime. His face is craggy, rugged. Merriment and sadness play across it in constant shifting patterns, the way those summer clouds, moving in the wind, might push light and shadow across the land.

I help my father from a car to a chair. He is stiff with spinal stenosis, shaky from late-onset diabetes, clutched by congestive heart failure.

There is something else I cannot see and do not know. Cirrhosis from secret late-night drinking sessions is scourging his liver.

In two years, he will be gone, and I will join the Dead Fathers Society.

At the moment, I feel only the twitching of life’s giant clockworks. I feel as though the very mechanism of life requires my father to slow down as my son accelerates.

It feels satisfactory and right.

Maybe it is, too, but not in the nice, neat way I’m imagining.

Now it is 1997.

Mockernut. Pignut. Shagbark. Tulip Poplar. Red Oak.

There are little signs on some of the trees as you roll through the roads of the reservoir. A year has passed. Today Joey is on foot, and Bob is in a wheelchair. He has grown sicker, and I take him on outings.

Today I am trying to wheel him along the 3.6-mile course of the reservoir, which takes in some pretty steep hills. Descending them, I lean backward at sharp angles, like a man walking wild boars on a leash. Occasionally I pop a hand loose from one of the grips to either throw or catch a squishy little football Joey and I are playing with as we walk.

I have come to think of these excursions as the Sandwich Generation Triathlon. Walk, Push, Throw.

My father has now been diagnosed. He is terminal. We don’t talk about that. We don’t talk about anything unpleasant, but my father can see that I have, for months, devoted my free time to him. I have driven him to medical appointments and taken him on these walks and slogged through shopping trips.

One day I take him to an art museum and dilate upon the meanings of the paintings. In front of a Winslow Homer, a pretty woman smiles at us, and I think she likes me for taking such good care of my dad.

A minute later I realize she was gently amused, because my pedantic lecture has sent the patient into a deep sleep.

Still, when he gets home he tells my mother, “It was like a different world.”

My dad is mainly housebound.

One day I wheel him around the neighborhood in the sleepy afternoon sun, and I sing Johnny Mercer songs to him. “Skylark,” “On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe,” “That Old Black Magic,” “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive.” He likes that a lot. I’ll never forget that day, singing to my father.

Occasionally, as we wangle the wheelchair through a tricky doorway, he will mumble, “Who would have thought… that you would turn out to be so useful.”

If you have a spouse, a child, a dog or two, a sick father, a worried and very tired mother, one way to get through a long, hard Sunday is to make a list of tasks. You start it at 6:30 A.M. and keep crossing items off, glancing down to the bottom of the list where there awaits, you presume, a paradise. You will park your tired self on a sofa and maybe watch The X-Files, because at least the guy who is part-fluke and who lives in the sewers will have a life slightly worse than your own.

Even under the iron rule of a list, Joey and I sneak in a bit of fun, tossing a football in a deserted parking lot and walking at dusk, with the dogs, into spooky, empty, snow-dusted woods. Just as the air around us fades from gray to black we stand in the pie-powdery snow on the banks of a chilling stream. And it’s so heartbreakingly weird and beautiful you wonder why people don’t come here by the hundreds.

And then back to work.

Last thing on the list: Bake cookies. I forget why. For school?

I’m halfway into the baking when my mother calls.

It’s 8:45 P.M.

My butt is feeling a sort of magnetic pull toward the promised land of the sofa.

“Can you come over? Something is wrong with Dad.”

Ohhhhhhhhh. For a brief moment, I am unsure which is the greater tragedy—my father’s ill health or the fact that I’m not going to sit down and watch television.

I drive over, and, indeed, he is failing in some ineffable way, dead on his feet, muddled in his head. I bring him into the bedroom and try to get him settled into bed, but his body flops and sprawls, starting to slide toward the floor.

I haul him up again.

“Let me try to get your head in the right place,” I grunt.

“I’ve always wanted my head in the right place,” he murmurs slurrily.

He’s about ten synapse-firings this side of a coma, and he’s still funny.

The next day I discover the interrupted cookies. They have congealed into a rubbery texture. Eating one would be like a hyena eating Gumby.

Things are worse, much worse.

I sit down with my mother and my father’s doctor.

“We should get hospice involved,” I say.

There’s an awkward silence. The doctor has to authorize this. He has to say that the patient is terminally ill. He has to say that the patient will not live more than six months. You can get extensions. They don’t send a guy in a hood with a scythe if you miss the deadlines. All the same…

“I’m reluctant to take that step,” he says. “When you say the word ‘Hospice’ to a patient, it’s almost like a death sentence.”

I look at him.

“Well,” I say, “he is dying, isn’t he?”

The doctor kind of shrugs.

He is an old-school guy, operates out of a big white house on a main avenue. He was taught that you fix people until you can’t fix them anymore. Then you let Nature take over and hope it’s quick. This idea of giving Death an extended booking, two shows a night with a pit orchestra, is hard for him to grasp.

My father, by all rights, should be dead by now, but my mother refuses to let this happen. When Dad begins to sag int

o a coma, she ignores the doctor’s advice and summons an ambulance to take my father to a hospital, where he is transfused and revived, just as Death was set to swoop in and claim him.

My mother is a small, unassuming woman with downcast eyes. In a room full of people you might miss her. I think it’s possible that Death underestimated her. She wears her hair permed up and back in a kind of sixties bouffant, dyeing it this shade and that, making all the stops on a subway line from blonde to auburn. My wife’s hair, by contrast, turned a silvery white in her forties, and she let it stay that way. Her face is utterly unlined, making her white hair seem as anomalous as my mother’s ash blonde hair hovering over an older face. My mother’s voice has stayed musical and girlish, in defiance of all the cigarettes she smoked, a pleasant echo of the beauty she once was.

The doctor now believes he is caught in an unpredictable crossfire between Death and this very tiny woman. He has absolutely no idea what to do, and his plan is to meet with us as rarely as possible, return few phone calls, and check the obit page to see if this mess has, by any chance, resolved itself.

It takes a few weeks of my jiggling the handle, and then my father is a hospice patient.

This means we are all resigned to keeping him comfortable, easing his pain, soothing his soul, letting him die.

Except my mother.

“I made a commitment,” she says, repeatedly. No one can remember hearing her make this commitment, but apparently it has the force of something you might say while pulling Excalibur out of a rock. The commitment includes keeping my father at home and administering medicines and meals with a precision and doggedness no hospital could achieve. My mother is Star Trek’s Borg Collective, a flying cube of quasi-mechanical imperialism. My father will take his medicine at the exact time prescribed. He will eat balanced meals, three times a day. Assimilate or be destroyed. Resistance is futile. My father lives an extra nine months or so because he is almost too busy to die.

My Father's Footprints

My Father's Footprints