- Home

- Colin McEnroe

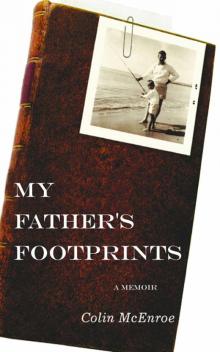

My Father's Footprints Page 13

My Father's Footprints Read online

Page 13

God help me, I am up there with a toy typewriter.

Some folks would rather be a wrestler or a fighter, but I would like to be a writer.

When my father is not writing he shows houses. It takes him away from me on weekends a lot, because that’s when people like to look at houses. Sometimes I tag along, and my childhood memories are splashed with the rattle of “For Sale” signs in the backs of station wagons and the aroma of freshly hewn wood in the brand-new houses and the echoing clap of men’s shoes on bare wood floors.

“I have to show three houses today.” Even then it sounds like an odd phrasing. I have to show you a place in the woods where diamond-shaped orange mushrooms grow. I have to show you how to throw a curve ball. I have to show you the place where I was born. But houses are so big and obvious. They need to be shown?

Missing is any mention of the people. My father always has to “show houses” but rarely to anyone. He doesn’t mention clients or customers because he is so hilariously a parody of the paradigmatic American Salesman circa 1962: good with eye contact, with names, with light chatter. My father is an introvert’s introvert. He prefers looking down or off into fairyland. He can’t remember the names, even, of his co-workers or our household pets. A cat of ours, Mackenzie, is still, after ten years, “the gray-and-white cat.”

When he pictures “people” in his mind, he pictures two-legged beings who bray out perfectly human—and therefore grotesquely irrational—responses to houses. They fixate on some quirk of a house’s appearance. The carpet, the kitchen floor, the wallpaper throw them for a loop. They cannot be lured down into the basement.

“The basement of a house tells its story,” my father explains. Water, strange fuse boxes, makeshift reinforcements to ancient joists, termites. These are the things you must behold. Once, he and I see a septic system out-pipe with a high-tech warning device on it, suggesting some imminent Chernobyl of poop.

“People don’t want to look at things like that in the basement,” he grumbles. “They want to look at the goddamned mullioned windows.”

For the right client, though, he is a godsend.

“We’d be pulling up to a house, and as we were slowing down, before the car even came to rest at the curb, I would say, ‘No,’ and he’d just put his foot back on the gas and begin pulling away, not a word from him,” says a woman who bought two houses from him. She cackles at the memory. “Any other agent would have tried to make me go in, see all the great features that weren’t apparent on the outside, all that crap. He just drove us away. I loved that!”

“How come you never take me to church?”

“We don’t go to church.”

“Other kids, their parents take them to church.”

“You want us to take you to church?”

“Yeah!”

So they do. It turns out that they mean “take you to church” rather literally. They drive up to the church. The car disgorges me. They drive home to smoke Fatimas and read the papers. They come back and retrieve me when it’s over.

They pick my denominations, although I am never sure on what basis. For starters, I am a Presbyterian, but later I will transfer to Universalism, get traded to the Episcopalians, and finish out my career, like Willie Mays on the Mets, as a Congregationalist.

They attend none of these churches. I am a latchkey Protestant.

This arrangement has enormous appeal to Bob McEnroe. Having enthusiastically repudiated his native Catholicism, he now has new worlds to conquer. He can be a heretic, an apostate, in several other sects. Each time I move to a new church, he reads up on its denominational theology. Then he shows up a couple of times a year and argues with the minister. Universalism, for some reason, is his favorite. The Universalist books pile up around his chair. He takes copious notes. William Ellery Channing should know so much about Universalism. The minister, a sweet-tempered old guy named Fiske, poor bastard, learns to fear the sight of my father coming up over the horizon at coffee hour, flying the Jolly Roger, ready to engage him on hairsplitting points of antitrinitarianism.

In seventh grade, there is an Easter pageant at the Universalist church, and I am Jesus. It is a speaking role. Cosmologically, nothing could be more second rate than to be a Universalist Jesus. It’s like being Nepal’s greatest basketball star. No one cares. You’re not divine. You don’t get the girls that the Methodist Jesuses get.

I believe my main job that day is to handle the “woman at the well” situation. I show up with my game face on. I am fully backgrounded. I spend the preceding Saturday night memorizing Jesus’ lines. I tell everybody what is what, as only Jesus can.

My father, sitting in an audience of fifty, is, by all evidence, enthralled. My later acting stints, in front of much larger high school audiences and working with slightly more challenging material and benefiting from better production values, will fail to impress him at all.

On this day, however, for reasons I cannot fathom, I have him in the palm of my hand. He will tell people, for the rest of his life, what a great Universalist Jesus I was. He will bring it up with me a couple of times a year, for the next thirty-two years.

“You know, you were a great Jesus that time.”

“Yes, you’ve mentioned. Has anything else I have done ever impressed you?”

“You just had everything under control that day.”

Is he putting me on? I have no idea.

He’s not always easy to read on this God stuff. When I am five, he overhears my friend Ruthie Saphirstein tell me there is no Santa Claus. He tells her—in a spirit of genial nihilism—that Moses was a fake. This is a joke, but it takes quite a bit of smoothing over by my mother with the Jewish families in our apartment complex.

Is our fimly HaPPy? I bet this work is h(e)ard, is it?

It is. It’s very h(e)ard.

So h(e)ard, in fact, that we are not getting anywhere with anything. Boy, does he ever have a lot of time to spend with me. Play catch? Go to the zoo? Bronx Zoo has Komodo dragons. Take a drive down there? See the dragons?

He is still funny. He is still in touch with little people.

At the real estate office, each phone has a row of buttons that light up in sequence as the lines are engaged. When the last button lights up out of sequence, he has divined, it always means that someone has tried to call the Harte Volkswagen dealership and has misdialed.

Once he figures this out, he makes a point of being the one to answer those calls.

“Ja?” he begins. And then, in a dreadful German accent, “Dis is der Black Forest Volksvagen Company.”

“Oh. I’m not sure I have the right number. Is this…”

“Ja!” And then he goes on at some length about the elves in the Black Forest, who make the Volkswagen parts with great care and pride in their magic.

Then he tries to sell the hapless caller a Volkswagen kit for $750. He dilates upon the money-saving advantages, the easy-to-read instructions, his willingness to lend the proper tools, and, of course, the everlasting gratitude of the elves.

He never sells even one kit because, near the end of his spiel, he reveals that the instructions, although easy to read, are in German. I suspect he occasionally crosses a line and begins to believe there really is a kit for him to sell. Boundaries are never his strong point.

Fourth grade. It is teacher conference day. I am home alone. Outside, the rain pours, cold and pitiless. The day hums with bad portent.

My mother steps through the back door. She is a swarm of wet bees. She is a demon hissing steam.

She shows me the report card. Many Cs. She shows me where a D—a D!—in penmanship has been changed to a C, with the teacher scrubbing off the epidermis of the paper to get rid of the letter written in ballpoint. The C is muddily inscribed on the paper’s festering wound. The grade change has not been occasioned by a reappraisal of my penmanship but by her bullying of the teacher. I have, in fact, D penmanship, but no child of hers is going to get a D. She says so. She will later find out that

Norman Mailer’s mother did exactly the same thing for him and imply that, unlike Norman, I have not quite held up my end of the bargain by becoming an irreplaceable fixture in American culture.

“Why are you so lackadaisical?!” she demands.

I am cowering with fear and remorse. My mind is scrabbling frantically at this word. I don’t know what it means. I picture a boy on a hillside. He has no daisies. His eyes are black holes of stupidity.

“I am embarrassed! I am ashamed that you are willing to be so mediocre.”

I don’t know this word either. I am blocked, stammering, stuck like Emperor Claudius on the first syllable of a reply.

“If you go on in this way, you will become a face in the crowd. You will go to junior high school and be a face in the crowd. Do you want to be a face in the crowd?”

I picture heads bobbing in a school hallway. In my mental picture, the heads begin to lose their shape, wrinkling like apples on the ground. The features of the faces blur into sameness. All of them come to resemble, vaguely, the little faces Señor Wences used to draw on his hand. They are still bobbing, bobbing, spasmodically.

“Do you remember those men in the Bowery? When you were in first grade? That is what happens to people who become faces in the crowd.”

Oh, God. Not them. Not those guys again. Help.

I must find out what lackadaisical means, what mediocre is. I must not be those things. I must not become a Face in the Crowd. I must not join the incontinent throng of my brothers in the Bowery.

She is, of course, juggling many complicated feelings. She is angry at me, but her greater wrath is reserved for my father. He is lackadaisical. He is letting himself become mediocre. He is no longer a remarkable boy. Our money is running quite low, and now she is working full time to keep us solvent. Every day, the things that made us all special are slipping, slipping away.

On me, her tirade works, from a somewhat ruthless perspective. I launch myself on a preposterous bends-inducing zoom to the surface. Soon I am near the top of my class. If my zeal flags, there comes, unbidden, the image of me, dirty, ragged, shuffling, unzipping my fly next to a green Pontiac. My zeal reestablishes itself.

As Peter denies Jesus, I deny my father. I deny my third grade self with the toy typewriter.

In seventh grade, I announce to my parents that I intend to become a lawyer. I am going to a private school now, with the children of many lawyers. I can see how they live. In big, chunky, Tudorish houses with mullioned windows. I will forge for myself a career based on certainty and reliability, not a bunch of goddamned elves. I will be the man in the Mustang convertible wearing the double-breasted blazer and the striped tie, not the man sitting in the living room at 1:00 A.M. in his boxer shorts scratching out dialogue on lined yellow pads.

My parents have pieced together some meager earnings and a scholarship to send me to this fancy school. They are hanging on to their cars a few extra years and skipping a few restaurant meals so that I can be a remarkable boy. And what does this get them? A son who cannot hide his own horror at the thought of becoming anything like them. A son who regards them as the Elephant Couple, abject mutants. Let their cup pass from me.

In my defense, I am terrified. At night, I lie in bed and my face burns with the fear of the next day. My status at the school feels so much more provisional than everyone else’s. I am on some kind of existential probation and a slip could push me right into the chute that winds through the school building and debouches into the Bowery, on Face-in-the-Crowd Street. And then I think about the way my face is burning. It can’t possibly be good for me to have my face burn like that, can it? Probably, I am making myself sick. I will die of Face-Burning Leukemia if I cannot get this under control.

Which thought makes my face burn hotter.

I lose my seventh grade grammar book. I cannot tell the difference between this and the early stages of heroin addiction. Either slip could put me in the Bowery. What will happen? The Council of the Burning Face ponders this all night. I cannot tell my teacher I lost the book. I cannot say “lost.” There must be some other word for what I have done. The night turns into a long vocabulary exercise.

“Mr. Friedman?” I say the next day.

“Yes.”

“This is Sandy Watson’s grammar book from last year. He lives in my neighborhood. He let me borrow it.”

“Why?”

“I mislaid mine.”

I look at the teacher. A smile is tugging at the corners of his mouth. He knows what a serious boy I am. The care with which I have chosen this word is not lost on him.

“Mislaid?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Does that mean you lost it?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Fine. Use Sandy’s. And try to find yours, okay?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And don’t use words that way. Use words to say what you mean. Not to hide it. This is English class, right?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then speak English.”

But I have already discovered lawyerly locution, haven’t I?

This lawyer thing is no idle fancy. By ninth grade, I have fallen into the habit of spending vacation days at the courthouse. Put on a tie, catch the bus, head downtown, watch some trials, take notes.

O! What is worse than a geek? A geek with designs.

I don’t require Perry Mason drama or James M. Cain heat. I don’t need sex-mad lovers and butcher knives. Nope. A run-ofthe-bench liability case will suit me fine. I watch a trial in which the plaintiff has injured himself opening a defective soda bottle. The bottle shatters in his grasp, ripping into his flesh. Could the plaintiff have contributed to his own tragedy by opening the bottle in some inventive manner that does not conform to the healthy laws of human understanding? What are those laws? I watch hours of testimony, as if the Scopes trial were unfolding before my eyes. Lawyers get up with church keys and pop bottles. “Would you say it was more like this? Or like this?”

For this Tribunal of Mammon, I have traded in the Court of Pie Powder. I have sold my birthright, my kinship with fairies, for a mess of pottage and broken glass.

I try to persuade myself that this is interesting. I am not a good enough lawyer to win the case. The soda bottle will never be anything but a soda bottle, and the witnesses will never be anybody but who they were. The best of the lawyers I watch have an imaginative flair, but, in the end, they keep their eyes on the ball. I daydream. Would you want a lawyer who keeps a pied à terre in fairyland?

Ah, yes, the fairies. They beckon. They sing in my ear. And then, one day, they bring me a present.

The present is actually a gift from my parents.

In retrospect, it may seem like the crowbar that derails my Lawyer Train, but that was never on their minds. They don’t dislike the lawyer idea. Sure, it’s a little crass, but a touch of crass doesn’t seem like a bad idea just now. The Romantics have been getting shelled, after all. Maybe it’s time somebody was crass.

The present is practical.

It’s a blue, manual Smith Corona typewriter. My first.

I’m not going to go into grandiose comparisons, but you know when a thing is right for you. A paintbrush, a baseball bat, a steering wheel, a rolling pin, a piano. The objects of our destiny talk directly to our hands.

That Smith Corona speaks to me. Tack tack tacktack tack-tacktack. Ding.

I will use it steadily for eight years. It will go to college with me and clatter under my fingers through long nights of term papers.

But it has one thing to say to me, right away.

“You’re not going to be any goddamned lawyer.”

Ding.

Five

Straight Outta Roscommon or Why History Can Be So Hortful

Sarah Whitman Hooker Pie recommended with this chapter

The Green Bastard

The protagonist of the preflight safety-features film on Aer Lingus is a peculiar, digitally animated man. He has nondescript red-and-blue clo

thes, short dark hair, a ball-shaped nose, and— this is disturbing—no mouth. Blank space where the oral aperture ought to be.

He does not speak, but even so the safety film seems to mock his mouthlessness. He holds up the tubes on the life vest, tubes into which one blows air. How is he going to do this? The oxygen mask drops down, and the narrator says one must place it over one’s nose and mouth. What mouth? Even when we are informed that this is a nonsmoking flight, the safety man is holding a cigarette and lighter.

“He has no mouth!” I say to the screen. “What was that for? To save money?”

Safety Man moves with great deliberation, a kind of robotic t’ai chi, in which motion never speeds or slows, in which the natural herks and jerks of the human body are cooled out. The animators have not solved the basic problem: Natural motion is imperfect.

Safety Man is also oblivious to the Sartrean condition in which he finds himself. Occasionally the frame pulls back to show him sitting amid rows and rows of empty seats. Safety Man is the only passenger on his flight. He doesn’t seem worried.

I am traveling to Ireland in April 2001. The flights do, in fact, tend to be uncrowded because Americans know, dimly, that there is (or may be) foot-and-mouth disease in Ireland and that this is either the same as or quite different from mad cow disease and that one or the other can kill you. They picture themselves placed on a pyre of burning carcasses, in a recently purchased Aran wool sweater. They stay home.

I’m going to Ireland, which, I admit, is a pretty hopeless place to look for my father, inasmuch as he never set foot on its soil. Still, as this book swims backward through time, I feel it dragging me back to the place we came from and the time we decided to leave. To Ireland, in 1855, when there were fairies and giants and banshees—in other words, when the contents of my father’s mind were real things afoot in the world.

My Father's Footprints

My Father's Footprints